Nirupa Bai Kawar, 52, an Adivasi from Chhattisgarh’s Korba district, has lost a lot to the South Eastern Coalfields Limited (SECL). India’s largest state-owned coal producing company, SECL, razed Nirupa Bai’s home down with a bulldozer in 2014, acquired her land for open cast coal mining, and denied her compensation or employment for years. But it also gave her two strong weapons—grit and resilience.

“The injustice to me and many others like me instilled in me the anger and the need to fight to get justice,” Nirupa Bai says. Nirupa Bai found support in Bhu-Visthapit Kisan Kalyan Samiti (Welfare Committee of the Land Displaced Farmers), a group of coal-displaced families across 39 villages in the Korba district that share a similar experience. While Adivasis had been protesting against the mining sporadically for decades, they formed this collective under a common banner with volunteers across villages in 2015. Since then, the Samiti (Committee) has helped build a movement against coal and its unfair practices in the region. Theirs has been a journey marked with moments of success and continuous resistance, especially around the Kusmunda coal mines.

Kusmunda mines are one of India’s largest mines, spread across Korba, about 200 kilometres from Chhattisgarh's capital, Raipur. Mining this sought-after fossil fuel comes at the cost of deforesting patches of forests in the region, which include Tendu trees (Diospyros melanoxylon), whose leaves are commonly used to make bidis (an inexpensive cigarette), along with Sal trees (Shorea robusta), tamarind (Tamarindus indica), and Mahua (Madhuca latifolia), a flower used commonly to brew local alcohol. These forests also provide livelihoods for the Adivasi communities residing here — a 2017 study found that forest produce contributed to the income of a large 83% of families surveyed in Korba.

“Our government has shown interest in moving to renewable energy and to leave fossil fuels, but why do they have to leave them after completely exhausting them?”

Land acquisition for these mines began in 1977, and the mine's production capacity has undergone expansion over the years. From 10 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) in 2015, the mines got approval from the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) in 2020 to expand to 62.5 MTPA. “Our government has shown interest in moving to renewable energy and to leave fossil fuels, but why do they have to leave them after completely exhausting them?” questions activist Lakshmi Chouhan, frustrated with new coal mining expansions in Korba. “We (the movement) will continue our fight against the impacts of this mining, and will continue finding support and hope in each other.”

A view of South Eastern Coalfields Limited in Korba-Trucks carrying coal to the Thermal Power Plants. Photo credit: India Water Portal CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

This new expansion will destroy 43 hectares of forests and displace over 9,000 families like that of Nirupa Bai. “Our ancestors worked so hard to make the land [we lost] cultivable by cutting through the hills and forests. How can I let companies take this land without compensating us fairly?” says Nirupa Bai. In their fight, the Samiti is demanding no more new coal mines and proper rehabilitation and compensation in the cases where the fossil fuel has changed the lives and livelihoods of communities.

Bhu-Visthapit Kalyan Samiti: A Fight for Their Rights

“I always tell people, don’t look for leadership, be the leader,” says activist Lakshmi Chouhan, also a part of the movement, as he explains the structure of the community-led Samiti without one-person leadership. “But, sometimes, there are a few technical things—like filing a case in court—which may seem daunting to some, so I usually volunteer to file them in my name. But in case a dharna (sit-in protest) has to be organised, groups of people within the movement get organised.”

A protest march by the Samiti, raising voices against the lack of guaranteed employment by SECL. Photo Credit: Rajesh Tripathi

Chouhan fondly remembers a National Green Tribunal order of 2013, which he thinks was probably the Samiti’s most significant victory. “In the order, the Tribunal quashed the MoEFCC-granted environmental clearance of the 1050 MW coal-based super-thermal power plant in Korba. We believe that was the first time in India that a full withdrawal of an environmental clearance had happened,” Chouhan says. A long fight held by the Samiti made it possible. The Tribunal, in its order called the clearance “illegal” before stating that the MoEFCC had “failed to anticipate probable ill impacts of the project, in conjugation with the pollution level caused due to the other projects already existing in the surrounding area.”

“As a movement, we also question the point of mining coal and investing in coal-powered thermal power plants,” Chouhan explains. “If you look at the state's power generation, you will find that Chhattisgarh is already a power surplus state. Then who is benefiting from this mining?”

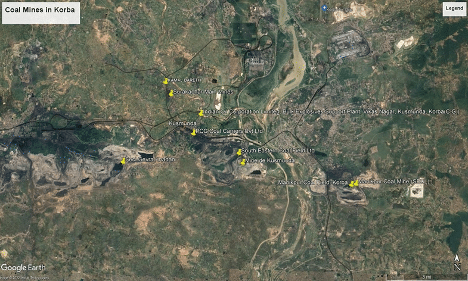

The many mines in Korba other than Kusmunda mines. Photo credit: Google Earth

In 2013, Korba had made it to the list of cities with a Comprehensive Environmental Pollution Index (CEPI) score of above 70, which indicates a ‘critically polluted area’. Even today, the pollution levels at Korba are alarming. A 2022 report found the air quality level of Particulate Matter 2.5 of the power hub to be about 28 times higher between November 2020 and June 2021. Nirupa Bai confirms. “There is just dust and smoke all around. The groundwater is polluted, we can neither drink it nor use it for any other purpose.” She reminisces about the days of cultivating her farms with sesame seeds, seasonal vegetables, and wheat. “After we lost our land and forests to coal, we’ve been buying all our food from the market. Our freedom to work on our own lands is gone, and now we live such restricted lives, working for someone else,” she adds.

Slow But Steady Road to Employment

Nirupa Bai now works in the SECL’s office. According to the Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy of Coal India Limited—the parent company of SECL— all those whose lands get acquired should be provided with fair compensation, along with either employment or a lump sum amount of ₹5 lakh per acre [approximately USD 6500 per acre]. It took eight years for Nirupa Bai to receive her fair share.

“Members of the Samiti helped me navigate the laws and told me that if I wanted to file a case in Court, they would give me full support. They also helped write applications and do documentation to apply for the job,” Nirupa Bai says. “At the office [of SECL] where I now work, company employees are aware of how much I have fought to get employment, so they don’t misbehave with me, saying 'oh, she is a fighter, let her be!'” Nirupa Bai laughs.

But the fight for employment in lieu of Kusmanda mines’ land acquisition for 628 displaced people is still pending. In November 2021, the Samiti, with support from the political party Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M), charged into the mining area of Kusmunda and disrupted work for 12 hours. As all mining work halted, SECL is estimated to have lost more than ₹50 crores [approximately USD 6.5 million] worth of coal production that day. This protest was in response to a broken promise, where SECL and government authorities had ensured the impacted people that employment problems would be solved in the next month. When the deadline passed with no solutions in the near future, the Samiti headed to the mining operations area with the CPI-M’s party flags. After this protest, four more displaced people were confirmed with a SECL job.

A protest by the Samiti in front of the SECL office, with a banner that states the name of the Samiti and the SECL mines. Photo credit: Rajesh Tripathi

“Now, my focus is not employment, it is justice. I will continue the fight for my land,” Nirupa Bai says, indicating the other key issue that has mobilised members of the Samiti—compensation for land acquisition.

The More Difficult Fight: Land

The land acquisition for coal mines often leaves the landowners stuck in limbo. “This happens because of a dangerous Section 11 of the central law, Coal Bearing Act, 1957,” Chouhan says, explaining why. According to this section, the central government has the power to vest land or its rights in a government company—like the SECL—by order. “The biggest problem with this section is that in many cases, the government takes over the land rights but doesn’t acquire the land. Often, the landowners are not even informed. But years after taking over rights, coal mining is yet to begin on those lands,” explains Chouhan. “The people neither get any compensation for their lands nor can they sell it. But in this in-between situation, the owner of the land loses their own rights to the land. They become orphaned from their own land.”

When it comes to compensating displaced families with land, SECL is finding itself in flux. It does not have enough land for compensation. In a letter written to the District Collector in 2019, the company requested the district administration with 200 hectares of land to settle the expected displaced people that would accompany the latest expansion of the mines. The Samiti’s continuous public meetings and demand submissions to district-level officers have helped keep the issue highlighted.

Public meeting held in Korba by the Samiti. Photo credit: Rajesh Tripathi

The company now seems to be slowly making headway—they have now decided to flatten 35 acres of the heaps of coal overburden accumulated over the years in dumping yards of the mines. Said to accommodate about 500 families, this will then be developed with roads, electricity, and a school for the displaced families.

The Bhu-Visthapit Kisan Kalyan Samiti is expanding its base. This March, they inaugurated a new office in a different village with the hope of bringing in more coal-displaced people and including more farmers, unemployed youth, and women. By the end of March 2022, they plan to meet an ambitious target of raising 50 committees, with 50 offices in 50 villages.

“I also try to provide the same support I received to other women who might be going through the same situation, who often ask me what documents to collate, who to meet, and how to win this fight. I’m not scared of anyone now!” Nirupa Bai says with a hopeful, confident laugh. “I will fight and prove them [SECL] wrong, the truth and law are in my favour, and I have the support of the movement.”