The rays hit the shiny black surface of a solar panel. The breeze is calm, the air is crisp and cold. It’s 1 p.m. in Little Buffalo, an Indigenous settlement in northern Alberta, and the sun reached its zenith. Eighty solar panels mounted on ten columns, all lined up, are strategically oriented to maximize exposure to the sun. They offer a unique and almost artistic display of technology to the passerby.

The panels have been standing in the grass near the community’s Health Center for almost seven years. The Lubicon Lake Cree Nation was among the first Indigenous communities in Canada to pursue an alternative form of energy by switching to renewable energy in 2015. They set an example to follow.

But, years later, what still fascinates this community is the context in which they decided to fight a giant with their means. The Lubicon Lake Cree Nation lives on lands extremely rich in oilsands. In fact, according to their government, the province of Alberta in Canada has the fourth-largest oil reserve in the world.

Alberta tar sands. Photo credit: “Alberta-tar-sands” by Visionshare is marked with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

An accident caused by this abundance drove a nation of barely 500 people to rebel. On April 29, 2011, rain damaged a nearby pipeline which caused a spill of 28,000 barrels of oil about 10 kilometers from the First Nation’s territory. It later became known as the largest spill in Albertan history in 36 years.

And so, Melina Massimo-Laboucan, a member of the Lubicon Lake Cree Nation, developed her Master thesis which included the implementation of 80 solar panels in her home community. To do so, she raised the necessary funds of 45,000 $ from various environmental organizations for a year.

Today, the system provides the equivalent energy consumption of three average Albertan homes to the Lubicon Lake Cree Nation. “It’s not about the size,” states David Isaac, president of W Dusk Energy, who helped set up the project during the summer of 2015. “In terms of the impact, the timing, and the location, those were far more significant. It was a symbolic project.”

To him, the solar panels reflect, above all, a shift in mentality, “transitioning away from oil and gas,” explains Isaac. “It really stands tall and proud in the community.”

The originality of the design contributed to its brand. “If you look at most solar projects, they’re usually quite boring,” laughs the president of the Indigenous-owned firm. “They’re hidden on routes, and you’re not going to be able to inspire people or elevate consciousness if you can’t see it. So having something visible and architectural is an important message to the industry to be more creative with solar.”

The community aspires to expand its network of solar panels in the future. “The plan is to have more solar panels when we get new buildings,” confirms Ramona, the addiction counselor at the Health Center.

In fact, a 10 megawatts solar panel farm is in the works. “We are applying for a license, and we’re still at the feasibility study part,” explains Darrell Ghostkeeper from the Lubicon Lake Cree Band Office.

“One megawatt could supply up to 1,600 homes, so multiply that by 10,” argues Darrell Ghostkeeper. With a population barely reaching 500 houses, the plan is to be able to sell the surplus of energy.

The 80 solar panels are only the beginning of the Lubicon Lake Cree Nation’s transition. Until then, the solar panels installed near the Health Center almost seven years ago will still be in place. They are guaranteed for at least 25 years, and up to 50 years.

The solar panels installed by the solar company Kuby Renewable Energy have a total capacity of 20.8kW. Photo credit: Kuby Renewable Energy (https://kubyenergy.ca/)

Decolonizing green energy

Indigenous communities wanting to take a step toward green energy and follow the example set by the Lubicon Lake Cree Nation can benefit from Indigenous networks rich in knowledge and resources.

Indigenous Clean Energy (ICE) is one of them operating in the field. Its mission is “to advance Indigenous inclusion in Canada’s clean energy future,” stated its website.

Their 20/20 Catalysts Program started with the intention of providing training to members of First Nations, Inuit, or Metis communities wishing to be prepared for a transition to renewable energy. The 3-month-long program led by around 35 Indigenous mentors from the energy field aims “to create clean energy leaders”.

A key element of the Lubicon Lake Cree Nation solar project is precisely that its members still retain their control.

“Melina became a superstar because that’s someone from the community, it’s not some foreigner,” explains Temitope Onifade, an affiliated research scholar for the Canada Climate Law Initiative. “It empowers Indigenous communities, they can say ‘that it’s one of our own doing that project’ ”.

This is not the case for many similar projects in Canada. Out of the almost 200 initiatives within Indigenous communities’ lands, very few are under their control, reveals a 2021 study by researchers at York University. “That means that we risk having the same problem we had with fossil fuels,” regrets Onifade. “The issue with oil and gas development was that it was mostly between the governments and the business partners.”

This system excludes an entity of the equation that will be most impacted by the environmental impacts, such as the spill in Little Buffalo. And this way of proceeding leaves its mark on people’s minds. “We see green energy as something bad because the way we learn about it is when they arrive in our territories and try to take our land,” explains Bia’ni Madsa’ Juárez López, a program manager for Keepers of the Earth Fund – an Indigenous-led fund to support Indigenous communities – at Cultural Survival.

Following the example given by the Lubicon Lake Cree Nation strays away from an established narrative which is still difficult to shake off. “The history of energy, in North America particularly, is entangled with colonization,” explains David Isaac.

This has shaped the mentalities “for many communities; colonialism has put us in a situation where we think everything needs to come from outside,” reveals Bia’ni Madsa’ Juárez López.

“The act of a community transitioning to renewables is very much an act of decolonization”

Lubicon Lake Cree Nation’s 80 solar panels represent much more than their energy supply. “The act of a community transitioning to renewables is very much an act of decolonization,” states David Isaac. “It’s powerful, it’s a lot more than electrons.”

Shadows along the way

On a more practical side, the reality of Canada’s electrical system can also catch up with a community’s desire for scale. Many Indigenous communities are far from cities, which is the case for the Lubicon Lake Cree Nation.

“If you think of the electrical transmission system, the major lines are like an arm. So there’s a lot more juice going through those, and a lot of the Indigenous communities are at the fingertips of that grid,” explains Ryan Dick, director of commercial and utility-scale sales for SkyFire Energy Inc, a solar company based in Alberta. “So my fingers are weaker, they can’t put up a big system. The lines aren’t large enough to power their whole community.”

The solution seems ready-made, go off-grid. “When a community has its own solar system, it’s easier to generate energy locally,” confirms Temitope Onifade.

But financial constraints can slow down the process. “Batteries are expensive,” states Ryan Dick.

For the Lubicon Lake Cree Nation, the absence of batteries to store the electricity has caused issues. Every time a power outage occurs, the Health Center has to shut down. “We get a lot of them,” says Ramona, the addiction counselor at the Health Center. Since the beginning of the year, the community has had at least five service interruptions.

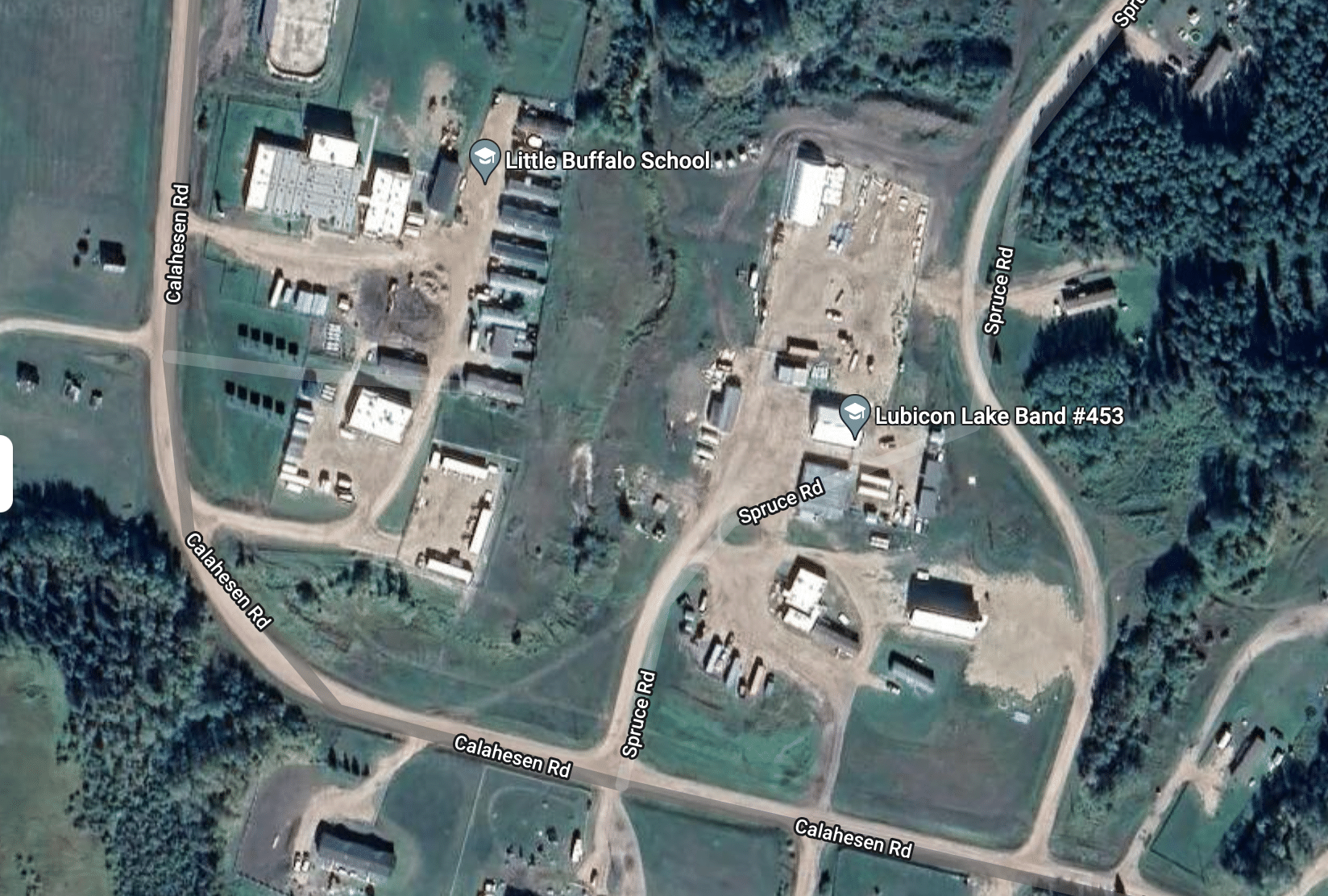

Solar panels and health center on Calahesen Road. Photo credit: Google Earth

Still, the community’s solar panels can heat and light a community building without much trouble. “Solar is relatively low maintenance,” says Ryan Dick.

Follow the lead

Across the world, solar energy has gained momentum in recent years, and Canada is no outlier. “I’ve been in the field for about 12 years, and it’s definitely a lot more exciting than it was when I first started in Alberta,” notes Ryan Dick.

The Lubicon Lake Cree Nation were pioneers, and they got it right. “Alberta is considered basically the solar powerhouses of Canada right now,” states Heather MacKenzie, an executive director for Solar Alberta, a non-profit society. “We anticipate having over 10,000 megawatts of solar in Alberta in 2024.”

The cost reduction would explain the increase in interest in solar energy, estimates Ryan Dick. Still, solar is far from becoming a central part of Alberta’s energy sector. “It makes up less than 5% of our electricity grid,” states the solar enthusiast, Heather MacKenzie.

David Isaac believes a change in policy agenda is required, and priorities need to shift to accelerate the transition towards green energy. And looking at how Indigenous communities are gaining ground in solar might be the way to go. “It’s about watching and learning from what they’re doing and then trying to amplify that,” explains Heather MacKenzie.